I am certain that the Washington Nationals will do fabulously in this year’s playoffs. How do I know? I moved from the DC area to Florida in January. Curses evaporate when I leave.

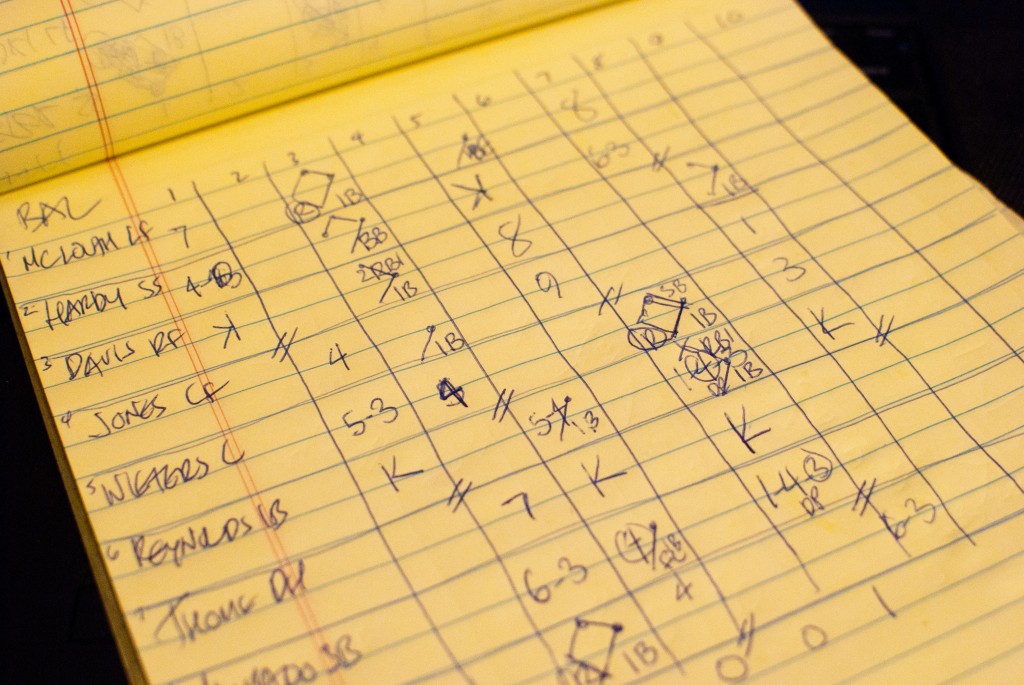

There’s precedent for this. After I moved to DC from Boston in 2001, the Red Sox built themselves into curse-destroyers in 2004. I suffered along with all of Boston up until then, and I didn’t even get to be there for the payoff! Now, several years later, Washington has its first playoff victory in baseball for the first time since trilobites swam the Potomac. I pondered this while faithfully keeping a scorecard for tonight’s Orioles-Yankees game. Latent dislike for the Yankees contributed to me pulling for the Orioles, even though their owner deprived Washington of baseball for so long.

Constructing a box score is one of my less marketable skills. Before politics consumed my life after I moved to DC, I was a suburban child in Boston who was a relentless baseball stats nut. I didn’t know it at the time, but spending my elementary school years poring over ways to compare pitchers to Pedro Martinez in Microsoft Excel seems to have foreshadowed my current job at a polling firm, trading left fielders for legislators.

I learned the arcane runes of the baseball scorecard because we didn’t have cable in our basement apartment in Needham and later townhouse in Norwood, Massachusetts, and even fanatical baseball towns like Boston don’t air every game over the air. I clung to a staticky radio that was almost certainly older than I was, the dial carefully tuned to WEEI 850 AM (where Red Sox fans have surely returned to an endless parade of misery and rending of clothing, now that the Sox have sunk into the cellar). If you could watch the game on television, you never needed to draw up a scorecard: the game was right in front of you, and chyrons did all the work of keeping you appraised of previous at-bats…but listening to even the most skilled radio announcer required a bit of imagination and visualization.

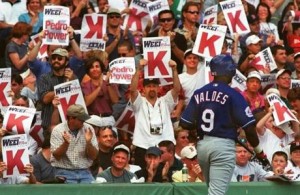

Pedro Martinez in 2000. Mark Wilson/Boston Globe

I remember the 1999 Boston Red Sox vividly. Just like how your first loves are seared forever in your memory whether you like it or not, you remember your formative baseball years when you first started obsessively tracking strikeout to walk ratios. I remember them vividly because I was eight, and had by then become well versed in the Curse of the Bambino, and the mythology of suffering it brought to flinty New Englanders. I followed them all season with my radio as if I was a child of 1949 and not 1999, and right as they came back from a 2-0 deficit to beat the Cleveland Indians in the ALDS, including a record 23-7 romp so ridiculous they started running out of numbers for the Fenway Park scoreboard, they lost the pennant to the hated Yankees.

This was one of the first tastes I had of the vengeful wrath of destiny.

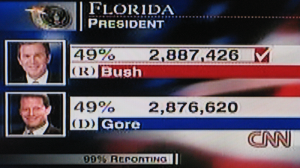

2000 came along, and another peculiar habit of flinty New Englanders aside from self-flagellating about the Red Sox captured my attention: the New Hampshire Primary (which triggers more use of “flinty” than any other event). I watched in awe as the primaries gave way to recounts Bush v. Gore and chaos, and I swore that every election going forward would be just this damn exciting. I took some colored pencils to an Electoral College map for the first time. Then in 2001, I moved to Washington, a city that didn’t have baseball at the time, and no cable package to keep up with the Red Sox, and even worse I was way too far to pick up even the faintest hint of WEEI. The internet simply could not do, and I devoted my obsessive energies to elections up and down the ticket and lost track of America’s pastime.

2000 came along, and another peculiar habit of flinty New Englanders aside from self-flagellating about the Red Sox captured my attention: the New Hampshire Primary (which triggers more use of “flinty” than any other event). I watched in awe as the primaries gave way to recounts Bush v. Gore and chaos, and I swore that every election going forward would be just this damn exciting. I took some colored pencils to an Electoral College map for the first time. Then in 2001, I moved to Washington, a city that didn’t have baseball at the time, and no cable package to keep up with the Red Sox, and even worse I was way too far to pick up even the faintest hint of WEEI. The internet simply could not do, and I devoted my obsessive energies to elections up and down the ticket and lost track of America’s pastime.

Even when the Nationals came to town I didn’t become obsessive again. I had known them, after all, as the hapless Montreal Expos. Eventually I realized after a rootless childhood that Washington, DC would be my hometown, but by then my interest in baseball had become part of my past. Times had changed, and I had new hobbies to eat up my time, but now that the Nationals bandwagon has picked up even the most jaded Washingtonians, I’ve started watching again. (Sure, heap scorn on me and my bandwagon clinginess, I won’t lie!)

The Boston Red Sox won the World Series in 2004. Now that I’ve moved from DC, it must be the Nationals’ turn. And who knows: if I managed to turn one of my childhood pastimes of coloring in primitive election maps into part of the paying job I hold today, maybe I can figure out a similar arrangement for baseball.